Austin Mass

In the west side desert, Cheney Pump Station

sits on the broken oil line northwest of Three Rocks.

Three Rocks is a long mile north

of the old oil line pumps at Halfway House.

South and east of the wreckage at Halfway House,

Mount Whitney’s west summit line connects through Five Points.

North and east of the Five Points

is the Four Corners and the J-13 dies there.

Quickly away from the corners using the 180 grade,

the Sierra rises and crests the Kings River’s canyon.

Further see the Sequoia trees.

I had a childhood fear of the Cheney engine.

I used to farm half ways between

Three Rocks and Five Points.

I used to steal trucks in to Four Corners

and escape down the J-13.

I used to white water river scramble

during flood years in the upper King’s Canyon.

And I learned to high jump in the Sierra,

but not as high as those trees . . .

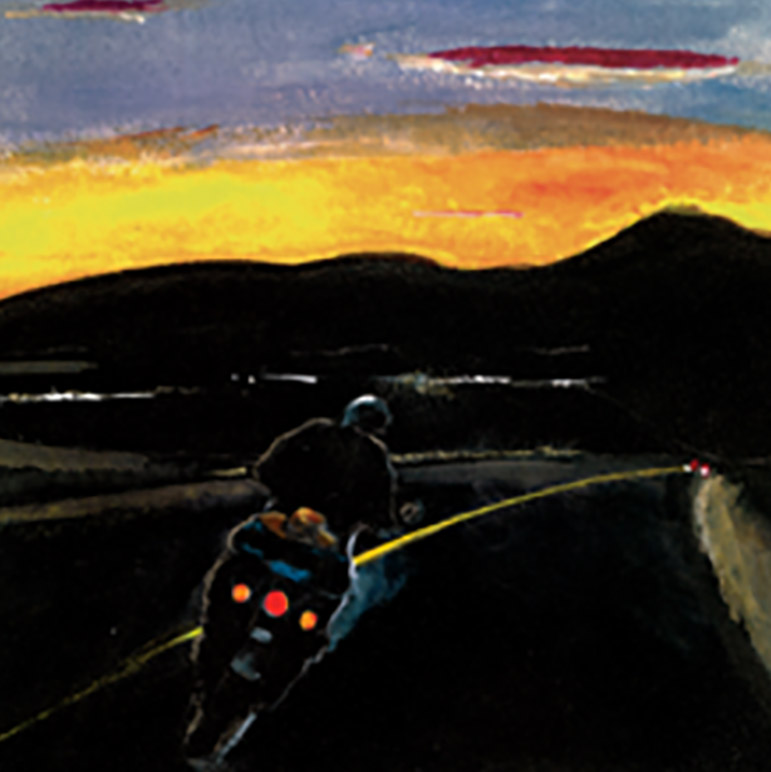

Mostly women drove the U-Hauls.

They’d pass in the dark with a traveler’s glance,

and the Buffalo rode easy through the cold.

Tired, I parked the motorcycle in New Mexican scrub

and slept till the afternoon sun woke me outside of Santa Rosa.

My mother was slowly dying back in Fresno,

but I bought coffee, gas,

and the Richard Reeves book on Jack Kennedy.

The rest of my day

went by the large round bales of hay farms,

with junkyards on the corners.

That night, I slept late by an abandoned cotton gin —

spent the following afternoon

reading about Kennedy —

slept there again.

The next day’s no conversation at the gas pumps

as the big trucks blew past.

And there’s a sulfur smell in the Texas air along I-10.

The Davis Mountains swallowed a pastel sunset in the distance.

I stopped and ate oatmeal bars

while the Texas light changed to a complete moon.

Back on the bike, through an endless land of lifted limestone,

an up and down geography of exposure from wind and rains.

Fort Stockton after midnight.

A couple of hours later outside of Ozona,

needing cigarettes, I pulled into a rest stop to roll Drums.

Smoked two, reorganizing my thing —

a ragged leather jacket wrapped around a flat brim hat,

and the Richard Reeves book on Kennedy

with most of a hundred dollars inside.

Noah’s old Water Buffalo had dangerous tags;

its tank was three-quarters full of gasoline.

I’d thought to begin writing in Memphis — or New Orleans.

But a Fresno poet named Luthor Rollins

believed their summer rains were too constant.

So I was probably riding towards Austin.

The next four hundred miles

detoured away from the 10, and it took

more than a day to arrive at downtown Dallas

at three in the morning, a quiet time

rolling toward the dead end — parking in back

of that knoll where the Reeves profile on power stopped.

Downslope, Dealey Plaza

seemed diminished at night with a softer kind

of yellow glow than the harsh Zapruder Film had.

The road looked steeper, and there was no one — quiet in the city.

I wandered alone on the Elm side

of a divided triangle common in street glow.

Zapruder framed Kennedy’s death in the sunshine

as the world changed when it was over from his right side …

a cab passed down the Elm Street about that slow.

I rode south from Dallas and stopped in Waco for fuel;

then the sun rose before my arrival

in the outskirts of Austin with sixty dollars.

Austin used simple street math, so I parked on the 24th,

resting a few hours in the shade under live oaks.

Refreshed, I caught a bus through tree-lined residential streets.

My seat was at the front, and there were many kinds

on and off at the stops before an old woman climbed on.

Wearing a pretty dress, in her late seventies;

she had fine white hair, a Northern European face:

a stroke victim inside her declining years.

The old woman nodded, taking my seat.

Over the next few stops I imagined her as maybe an Anne —

possibly a widow in the dawn

surrounded by early bed light and their old things —

maybe on her way to the midday symphony …

because she’d played the oboe, but her oboe had been put away.

Then the driver dropped me south of the Capitol,

next to the river with my first Austin story framed behind me.

Looking north from a smaller Colorado,

the Congress was a long avenue lifting to a dome.

If the river was zero, the Capitol might be the 12th or 15th Street.

A few blocks away, Rueben, a street man,

knew where to get coffee.

He said over on the 7th Street

in the old warehouse area

where truck docks were turned into bars and clubs.

The Asphalt Café used six of my sixty dollars

for an average sandwich and some coffee —

I was caffeine-driven until three

in the morning reading Reeves again.

After the café closed,

I walked west on the 6th Street

past used cars and a wall

with a glass mosaic of an Austin street man.

Moving closer, I discovered the mosaic was made

from bottle ends and the artist signed himself as Night Train.

Looking for shelter off the 6th Street,

I went further north past houses converted to law firms,

and found shelter in a Lutheran schoolyard near the 15th Street.

In the daylight there was a tunnel next to the jungle gym.

I walked back to the 24th and drank more coffee,

then rode the Buffalo downtown,

weaving in and out

of jarring traffic on Congress

till rush hour slowed us all to a crawl.

Traffic crept forward in solid lines through the morning swamp.

Red-suited Texas women strode down sidewalks

like they’d come from cluttered bathrooms.

After parking, I went against them

while they looked through my farm clothes.

Politics was the same new conservative

except for downtown’s better core of old.

Austin trash swirled after lunch;

off in the distance, scattered clouds

made it a humid rainfall country.

Back on the bike,

riding to the east side of I-35,

midafternoon rain poured from the trees.

I parked on a greasy side street in front of a bar —

a kind of damp, smoky place that played Ray Charles.

I drank sparingly, nursing the cash.

It poured outside the Austin bar for several hours,

and I returned to the Lutheran schoolyard after dark —

it seemed wise to be gone from the tunnel by sunrise.

A few hours later, the click sound

of halogens woke me to another storm.

It was raining out there, and a police car turned at the corner.

I saw a flattened leather ball by the jungle gym

that must have bounced strange and rolled wrong for quite a few.

Opening the Reeves book to a blank page,

my watch looked like two o’clock when I spoke out loud.

Phrases come as odd lots.

I started jotting them down in the Lutheran yard.

Tried writing out of gas in the garlic sacking crews,

where postwar Indochinese men

sacked on even days,

women sacked on the odds.

Watched them work their asses off

to pay for growing snow peas.

They were additionally financed

by refugee resettlement acts.

I went ahead and wrote that stuff down —

before deciding to get to a shelter in the morning,

to get what’s needed, and then get the hell away …

At sunrise along the Congress,

a street woman didn’t care where the Shelter was

and wanted to be left alone.

Then the morning sun rose into clouds,

and better-dressed people ignored me.

Some “night trains” were leaning against a bank.

It felt more natural asking them —

they said the Salvation Army

was over on the 8th Street,

against the traffic court and I-35.

But the Shelter wouldn’t accept for another hour,

and the “night trains” needed a smoke.

I never got their names

as we smoked my next-to-last one.

One man needed a dollar.

My state of mind was almost out of cigarettes,

and I couldn’t help him —

walking away as morning crowds gathered in the city.

I smoked the last on a bench

as several buses passed every half hour

and a crane added layers to a building.

During the rush hour

a bus discharged a black man dressed in gray.

He hesitated for a second … seeming pleased,

steppin’ down to the pavement —

throwing old air out and taking new air in.

The same carbon black face as baseball’s “Cool Papa” Bell,

his clothes were state issue.

He sat down beside me, silent a little while …

clearing his throat before calling me sir, which amused me.

Released from prison yesterday,

he wanted to know where some shelter was.

When I told him about sleeping in a Lutheran play yard,

he said his name was Max Gonzales from a Huntsville prison.

He sat looking around like a man who’d been away,

and spoke in complete sentences, noting our cars had changed.

Then our conversation evolved

into Luthor teaching poetry at a California prison,

and Max said there weren’t any poems in his cell.

When I asked him what he wanted to do,

Max said he wanted to be a cabinetmaker

and asked about me:

“I might try writing.”

“Why?”

“It’s cheaper than farming.”

Max laughed and asked again

if I knew where the Shelter was.

Another storm was coming, so we started walking,

clouds covered us with a quick rain — toward the Capitol,

we turned right for the Shelter.

Six more blocks uphill in the wet,

till Max asked a man

who pointed at an impersonal structure

rising like a four-story warehouse.

Max said it looked assembled on sight —

with the same tilt-up construction technique

that prisons used.

I wondered if the beds were clean,

but Max told me to keep my mouth shut in there.

The concrete enclosure seemed about five years old,

yet the steps were middle-aged.

Up the stairs with wet clothes, they let us in.

The Shelter was pitted walls and frustration smells

with buzzer doors having crisscrossed wires in the glass.

We were called clients —

there were forty of us in the foyer, maybe more.

A blend of screaming and shoving

with a little Spanish chingaso and some fuck you.

We used our ears in a simple exercise figuring out the rage,

and Max guessed the winners sat in chairs

and the losers stood arguing with the winners of those chairs.

Arguments and pissed-off tension veering to indecision.

More bullshit when everyone heard the fiction and nonfiction

of an ex-soldier passing a radio around,

saying tubes made a warm sound …

Max handed the receiver back with a smile.

Then up through the old clothes and iron hair,

harassed shelter monitors passed out numbers

from behind a steel credenza.

One bellowed at us to stay

within the painted lines of a reinforced floor …

We did, standing in twisted shadows from damaged overheads,

while the man ahead of us had lost his bicycle in Round Rock

and the man behind us came in to bathe.

When we got our numbers,

we were number twenty-four and -five

through the wire door.

The other side opened to a cavern

where street noise evolved from

disagree to violence in the back alley.

Down the stairs, a quick sideways glance

at a wall hung with clammy clothes.

Did we need to see elderly men in the open showers?

We did — and still wore damp clothes at eleven a.m.,

with Pine-Sol odor at the written check-in.

Two hours of standing around another credenza

before the process woman wrote us into

Lane’s Job Searching Class.

She ran the elevator too and then unlocked

the steel door at the third room.

The process woman told us,

so we’d know where we were —

no humor in the eye contact.

Inside, we smeared our language on forms —

while Lane said he’d served on submarines

and introduced us out loud to the class,

who didn’t care who we were.

Lane had a depressing pallor and weight,

in a windowless room — no view and pass/fail like high school.

And everyone wore the same kind of tennis shoes.

When Lane asked, I mumbled the cover lie of a broken motorcycle;

then his eyes teared up, saying, “That’s just too damned bad.”

He told Max at the break how the Shelter saved police man-hours.

Lunch, was food in the noise,

and a classmate wanting my Reeves —

she called herself Hope, telling me her name twice,

and kept the book under her sweatshirt.

Hope left the Alleghenies after tenth grade,

before being raped in New Jersey

and driving Freightliners out of Shreveport

to pay for tattoos in New Orleans.

Later on, she became a thin woman

topless dancing near Juarez

and buried her dog on the rock hill of Oatmeal, Texas.

A confusion of voices over a pale yellow stew,

and my filling broke on hard bread.

No knives used, as most heads stayed down

in a sea of disagreement over the spoons.

Discarded empty plates in the trash cans

with mentions of God.

Down the hall, Salvation Army commanders

dressed like admirals, and I’d almost forgotten where I was.

That afternoon Lane had us practicing interviews for jobs.

The Shelter’s most useful rule

was “shower before bed or be evicted as unwashed” —

so we were a naked mass in a group shower.

I slept with forty-two clean men that night.

The adjacent bunk had a congested Stanford lawyer

who’d served time for grass,

and above me a mechanic saving his money for tools.

In the half-light, ex-clients called “monitors”

paced between the bunks, watching us out of gas on our mattresses.

A fight woke me to two thieves stealing the same pair of shoes.

Shouting monitors solved the shoe chaos.

Then — just as Max said — it was “quiet down” in the voluntary jail.

At five-thirty we ate breakfast donations

while someone threw chairs at the overheads.

Later on became morning job exercises,

and that afternoon everyone passed the class.

On the third day, Lane set me up with Rashmon

over at the Labor Hall on the 2nd Street for some cash work.

Rashmon wore dirty white shirts, shaved badly, and got screamed at.

He used a morning number toss for your place in the work line.

I lost Rashmon’s toss and went outside to the parking lot.

Overcast above the homeless men on the asphalt,

as they surged around a contractor bellowing “fence holes.”

Failing to break through the crowd, I heard

someone else’s “garbage cans.”

Dove in to say I’d do it, and got in a truck

to paint garbage cans green.

On my fifth day in the Shelter,

I walked into the Labor Hall and lost the toss again.

Outside, there was too much anxiety

in the crowded parking lot,

so I bought my way through the noise

to the river with three cigarettes.

I found peace near the running paths

next to traffic on the 1st Street.

After a few hours beside the sand-colored water,

couples mostly ran back and forth

beside the Colorado between two weirs —

small dams that slowed the surface to a fluid mirror.

Maybe they were Lyndon Johnson’s weirs.

The upstream had an old power plant

with concrete verticals and aging stains rising from distant trees;

downstream, I felt kind of outside of things,

while an eight-man shell rowed beneath an Austin bridge.

My restless journey across the Southwest

continued to a smaller Asphalt Café,

northwest of the Capitol by the 24th.

I drank coffee inside, before leaving

to get fresh clothes from the motorcycle.

Most nights, after curfew in the Shelter,

it was cigarettes in the common,

like the old jail yards Max said.

A yellow line divided us from women,

while a monitor mopped a mess in the corner.

So we were smoking near the harsh ammonia,

while across the line, a young Kentucky girl offered herself —

a feminine nightmare with skin disease —

and the mop man enjoyed her.

Most of the women were usually beaten crazed

or ruined young, and some were just stupid

like the Kentucky girl.

Most nights, Hope stumbled over the line for a smoke,

blowing plumes of stories from the women’s floor.

Her dry hacking cough mixed in

with screams and scratches over a fur coat.

Smoke mixed in with bleeders from the gums

flushing their guts away — too much for Max,

and he turned aside as she got to the dead one.

Hope just kept going through it,

talking woodenly about them as children,

and I was thoughtless of my own.

Lane called me in on my eighth day in the Shelter:

“Rashmon’s got something for you,

but it’s complicated and strange — a little patience.”

“Fine, what is it?”

“Well, there’s a roofer takes our people in.”

“Who?”

“Leo fixes roofs. Meet his man Brian in the morning.”

My long week in the Shelter

meant much more than a turnstile

for saving police man-hours —

I wished Max well and left at dawn.

Outside there were “night trains” asleep against the walls.

A month later, Hope still lived in the bedlam and avenue grime,

while Lane’s records indicated Max made rural chairs

out in Dripping Springs.

But when I checked there,

no one knew who Max Gonzales was …

I waited with a dozen men in the alley behind a gym

till an oily red flatbed skidded up.

“Good morning Brian, where’s the boss?”

“Not here Roy, check out the truck, please.”

The red Ford had vise grips wired to the hood;

then the hot smell of antifreeze around a grimy motor —

two quarts down, no air filter.

I got in and sat in the filthy passenger seat

with my knees up to my chin because of trash on the floor.

The boss roared up in a single-seat car,

burdened with tools and rolls of tarpaper —

wild eyed, he got out, barking,

“That red Ford got oil? water? Let’s go,

let’s go — stop, stop, stop — tighten those studs,

ladders. Let’s go, Brian, move, tools, move.”

I stepped out for Leo, a tall thin man

stooped around bright suspicious eyes;

a mild speech impediment solved by hollering.

“Hi ya Roy, gotta smoke? You a farmer? good.

I been around, done some, seen some —

haven’t seen it all, seen some.”

Gray ponytailed hair down to his waist,

out of cigarettes, maybe a loud pain in the ass.

“Gotta smoke? Let’s go.”

I liked him.

Brian told me to ride with him; and I made an enemy

clearing roof trash and tools off the floor

when I got into the passenger seat.

Later, James, the huge black man, told me the seat was his.

Brian seemed nervous as we pulled a hot tar kettle

that appeared from the shed, followed by Raymond, Leo’s father,

in an old green Chevy one-ton with crooked white doors.

A cracked side mirror showed it hauling a load

of smiling men down the tree-covered alley.

And as they followed us around the corner,

a white door flew open to hit a pole —

a God dammit came from Raymond’s ravaged door.

Then we were a procession in sunshine

to the gas station for Celia’s coffee — all of it.

“Celia, this man’s Roy Ruth, he works for us.”

“Hello Mr. Ruth, seventy-six cents please.”

“Thank you, Celia.”

It took all of rush hour to get to the job,

where a myriad of commands backed the kettle down the drive.

Leo had his ways, and the kettle was still warm from the day before.

The propane burner was carefully lit by a man named Castro.

He managed the fire, loading solid kegs of cold tar

and got them boiling thin in half an hour.

The day became a small hot tar for most of the crew,

and later a tear-off for Camey, Brian, and myself;

the roof was already taken down a couple of layers.

Men unrolling tarpaper or hauling 90-pound buckets of tar

down the driveway and up splattered ladders to the roof.

Flood the paper surface with mopped boiling tar

as glue for heavy modified paper; strap the perimeter with metal;

nail that. A 140 degrees — hot tar roofing.

Men furiously working, hot, haul the trash off.

Leo left. Camey, Brian, and I left to the next job.

On the way, Brian gave me bread to eat, saying,

“I’ve got creative writing this morning.

Most of our jobs are hot tar,

but Camey and I will teach you to tear-off —

be careful, it’s Leo’s test.”

“What’s a tear-off?”

“Tear the old shingles down to the slats.

This one’s old, Roy, a four layer.”

We tore some off and slid it over the side into the truck.

Leo appeared, gave me cash to eat, took Brian to class,

leaving Camey with me —

a smart guy smiling at my tattered Spanish.

After lunch, John Joe Monroe replaced Brian.

He talked a lot and hated Mexicans.

“My wife’s Leo’s belly dance instructor.

I’m special, and my new tattoo’s infected. Got any grease?

Leo needs me to run the big jobs.

I’ve been in prison, ’n women like me.

I’m a carpenter, builder of anything.

Where’d you get that bike?”

“In the Devil’s Den, John Joe.”

Then Monroe mentioned riding those Indians and Beemers,

chased the niggers through the Poconos and Catskills,

lumberjacked there, fished off Florida; then last month

met his third wife at the Rainbow Gathering in New Mexico.

“She needs stability — I give it to her and our kids.

The father’s comin’ next week — he’s an asshole.”

John Joe Monroe was the dumbest fucker I ever met.

The rest of the crew arrived about three

and ripped off more of the roof, peeling shingles

or standing on the attic rafters

to shatter the shakes above with shovels.

Leo saw me fading in the heat — gave me yellow pills …

a minute later yellow sweat streamed from my forearms.

At five, the truck was full, tarped, and tied;

and the crew enjoyed the ride to the alley,

where it was payday.

“Brian, I don’t want any tools,

anything overnight in these trucks.”

After the men were paid,

Leo had me drive the trash to the dump —

a slow, humid hour out of town through the gate.

Austin’s refuse drew scavenger birds and swarming flies

as yellow crawlers and sheepfeet packed down the limestone dirt.

The wasting mounds were a moon ruin over plastic sheets,

layered and buried underground to trap the poisons.

The sign said to unload trash by hand

till their skiploader could find the chain and pull out the rest —

it did, and I found my way back though heavy traffic to the alley.

Almost dark when Leo hollered from the trees,

“Roy, there’s work tomorrow, need cash now?”

“Nah, I need a place to stay.”

“Are your chakras and path clean?”

“Not anymore.”

“Well, you can pitch a tent in my backyard.”

It wasn’t too far from the gym,

so I parked the Buffalo in his driveway.

Leo’s yard had limestone walls under tough oak trees.

We spread out a roofing tarp in the weeds, set the tent up,

and put a plaid bag inside with a Punjabi pillow for my head.

My rent became a case of Guinness every month,

and I read with a two-stage camp light

and ashed into a Drum can.

I rode to the Asphalt Café the following morning:

an iron counter with motel ashtrays on scarred tables;

there was also the usual monthly art on dirty walls

around a grimy nation of squares for a floor.

After buying an endless refill from the Hindu barista,

I found a dog-eared critique by Garry Wills

on Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural,

and spent all day reading that —

which explained the pair of political poems

as what the war became and Lincoln’s explanation why.

My next few months

were chaotic mornings loading trucks, before entering

a badly designed entrance off of the 42nd Street —

merging blind into I-35 with shattered mirrors

on an overloaded truck.

Our first really big job was the Comic Book Store;

most were old warehouses converted to bars and clubs.

But sometimes we had payroll delays;

Leo’s crew were unusually patient as he hesitated —

a month, then five weeks,

while we got a sheepish forty dollars here and there.

Leo finally arrived with $22,000 in a shopping bag,

counted out on Raymond’s filthy hood —

scrawled notes, payroll memories, whatever …

everybody paid.

After work, I sink-bathed most evenings in the café

and read a thousand pages a week.

Brian’s borrowed library card got me into Boorstin,

anthropology, and desert Gods; Korea, Bukowski,

some crime trash, and twentieth-century general history.

By December, I’d made a barista friend

named Eleanor, an oil painter who’d flown her dog

into Austin for nine hundred dollars — Ito on downers.

Ito died in a farewell room at the veterinary hospital.

I never knew her.

Then Eleanor wasn’t around after New Year’s.

Intelligent Moe said she’d been at home

stretching canvas over frames.

Weeks of painting before a progression evolved;

another month till they were hung in the Asphalt Café:

twenty-eight retrievers in four parallel rows,

her paintings ran left to right across

the south wall —

starting as real and changing to surreal

in a smoke-filled room — while I wrote by the best middle dogs.

After several months in the Austin mass,

all I had was motorcycles and tractors in the same patterns.

The next morning got spent writing cowboys, women, Bob Wills,

and oompah-pah at a chicken dance that was a waste of time.

So I wrote about a café dog

named after a starstruck L.A. judge.

Ito was a homely brown dog

with nice eyebrows and black lips.

She usually slept by the front door

and shed several dustpans of hair every week.

Ito also had bad teeth, an unpleasant stench;

and yes, her anal glands were especially expressive,

so you had to listen to her working on that all night.

But after developing a cough last year

from congestive heart failure and lung cancer,

it was time to put her down.

So Ito got bathed and walked around the block —

she cost $30 for shots

and $105 through the oven.

Their invoice said that Ito weighed

46 pounds going in,

60 ounces coming out …

An old woman on the bus took my seat

surrounded by her bed light and her old things

I named her an Anne, maybe an Anne

A great looking woman ready to die

Maybe a widow in the dawn

who’d played the oboe, but her oboe’s gone

I named her an Anne, maybe an Anne

I hope she gets to the symphony

A mile south of the tracks

by an old schoolhouse full of the past

she put it all away, her oboe’s gone, her oboe’s gone away

An old woman on the bus took my seat

surrounded by her bed light and her old things

I named her an Anne, maybe an Anne

I named her an Anne, maybe an Anne

I named her an Anne, maybe an Anne

Time passed and my situation changed.

Landis was a slight musician with careful hands.

He rented me a couch, played six strings,

and read political history

a block away from the Asphalt Café.

A bad cook, his people were politicians.

After leaving school he’d returned to the guitar;

now he played in the back room

while I wrote by the front door so we wouldn’t trip

over each other in his small, grimy space.

Books and picks were everywhere.

Both of us stayed poor,

sometimes eating back alley food —

as a couple of fools arguing over pizza boxes.

One night we found a case of beer

and had a few for the postwar farm changes,

another for the music in the bathroom.

We were a winter absurdity enjoying the beer —

and our money came from moving rocks on two-wheeled carts,

which was sporadic work and barely paid the rent.

The following week, Landis took me to

a cold-night campout — a hundred guitars playing

around a Hill Country fire till boss Jay took over,

allowing two guitars at a time under the stars.

Back home, the Two-Guitar Rule became my metaphor

for simple things written on shopping bags.

My punctuation was overdone;

I recalled Fresno nuns from far in the past

who would’ve had issues with commas everywhere —

they’d probably suggest more and’s.

Instead, I asked Landis about semicolons.

Wiping down a guitar, he looked up to say,

“Mary had a little lamb; semicolon;

the animal had white hair. Period.”

“Thanks, man, now I’m better.”

Then the roofers hadn’t been seen for a couple of months

till I saw Leo one day over on the 15th Street —

he looked a little sideways.

“Hiyya, Roy, we still need some rains —

first time I had to tell the crew to find

other jobs for a while.”

Hollow-eyed he continued,

“Raymond’s old truck blew a head gasket,

so did he — we got to have rain, man,

my old cats are staring the clouds in,

purring for the big ones;

but it rains somewhere else, not here.”

I thought about this for several days — overcast rainless days.

Leo’s crew were deserving hot tar roofers without a reason for cover;

besides, I owed Leo twenty-four dollars —

maybe a rain prayer could help Leo’s cats witch the rains along.

So I wrote in a time of blooming warmth:

We need warm rain, we want informing rains,

rains for obligations.

Rains to remind people that water ages cover.

Other places have painful floods;

we have lowering streams and diminished flows.

Don’t send a hurting wind rain,

just a reminder so people know where the water goes.

If the rains come, we can return to boiling tar;

our money can take us overseas.

And while we’re gone,

Raymond’s heads will be sealed

and Burning Man won’t seem so far away.

We need drizzle water — rain words that run to lows.

Desiring a gentle Tuesday storm for roofers,

Thursday weather turned to cold and sleet,

while my debt to Leo remained twenty-four dollars —

I guess we all need rains for obligations.

We need warm rain, informing rain,

rains for our obligations …

No more lowering streams and diminished flows,

just reminders where the water goes.

Just reminders where the water goes …

send us rains for our obligations.

We need warm rain, informing rains,

rains for obligations.

No more lowering streams and diminished flows,

just reminders where the water goes.

Just reminders where the water goes …

send us rains for our obligations.

Ahhh ah ahhh.

How’s the goddamned sky?

A couple of weeks later

it was a cold morning walk wearing Birkenstocks

after cold sleet changed to ice, making it slick on the sidewalk.

I limped sore-toed into the Asphalt Café.

Landis was staring at the ice, and he looked sick and pale.

I asked him why.

Landis said it was last night’s wake.

“Wake?”

“Well, Dave Redmond fainted and his girlfriend

found me in the phone book.”

So, they carried unconscious Dave

out of his bathroom, loaded into his car,

and took him down to the Austin hospital —

where the CAT scan read burst aneurysm all the way.

Dave died at three o’clock.

Then Landis played a bar

where the musicians knew Dave Redmond.

After it became Dave’s wake, a customer wandered into the music,

saw and heard the odd strains, and asked why.

Landis told him it was a wake for dead Dave Redmond;

the customer’s eyes tightened as he murmured

“What’s goin’ on?” and that his name was David Redmond —

the CAT scan tech for a dying man with the same name.

Shook him up so bad: he’d gone to that bar to relax.

Outside, Austin was closed down by ice storm.

We left the café, wandering a few blocks to the restored capitol —

they’d reworked the joints and columns in the legislature,

but the halls were lined with pictures of old men.

We went past them, talking about segregation

and the “One Man, One Vote.”

On our way through the legislature,

echoes under the rotunda reminded me

of my grandfather’s house —

then the rough Texas paintings of white men

showed us out of the capitol

with no more mention of Plessy v. Ferguson.

Outside on the cold ice again,

we slid past law firms and my old Lutheran yard;

and turned the corner into reconstruction

of the intersection at Congress and Martin Luther King.

We counted six heaters helping red-faced men

make overtime on the backhoes —

then Landis wondered if the farming was like that.

No, our heat came from burning stakes in barrels —

why those buried water lines cost several farms just to build,

and you’ve got more fingers in the urban pie

with less speed than the rural.

We looked around at the average Southwest

or the white man’s Mexico

and left the operators to their backhoes.

Up the street, he refined our history even more,

walking four blocks to his university’s memorial:

“Rita No. 8” was one of the old crude-oil pumpers,

salvaged from the East Texas Oil Field,

which endowed the university.

She represented the revolution of oil,

as the guitarist stood beside the huge

squared oak of her counterbalance,

marveling how the rig was a single tree

that paid for school.

We wondered about overdrafting the field

with roustabouts from Carolina,

waiting for Ohio to send more steel.

Could Rita remember the twenties?

And if she could, would her counterbalance beam

balance down for running our cars and utilities

or balance up for school?

We left there too, heading back to the café.

Landis asked for a legend. He needed

one — we all do — it’s freezing.

Something for a pair of guitars, and he’d pay in Guinness.

I was almost ready to leave Austin,

but my writing hadn’t shown what it needed to.

So I kept trying different things in the Asphalt Café —

tried wooden tables out of prison years based on Max Gonzales,

then I chased my son through a farm dream.

But they were put aside as I wrote for another week in the café —

alI I’d gotten was Anglo-Saxon

over Romance language and the “So What Rule.”

“You all right, Roy?”

“I’m sorry, Eleanor.”

“What’s the ‘So What Rule’?”

“Ahhh, sometimes it’s written beautifully,

doesn’t say fuck all: the ‘So What Rule.’

“Have a beer, Roy.”

Sunday morning I started writing under the middle dogs;

swerved, then began again with the phrase

the hot tar life …

writing on a pad all afternoon and into the evening.

I broke for a movie called Dr. Strangelove. Liked it.

Then finished the piece on the sidewalk that night. Liked it.

It wasn’t the legend Landis required,

just a long untitled paragraph.

I read it out loud to Eleanor

over a morning beer, an’ she liked it.

She needs more roofing, Roy, try stacking it as verse.

The next afternoon,

Intelligent Moe served Landis

a pitcher of Guinness and some little fish crackers.

Behind us on the dirty walls,

there wasn’t any legend in remove and recover —

just a dog in a woman’s arms still evolving left to right.

Landis read the first page;

I sauntered over to the middle dogs.

He ate his little fish, sipping beer,

reading, handing the pages to me when I came back —

recording the hot tar piece was my Austin close.

Landis thought those industrial guitars

should be called a “Roof Sun, Spoken” …

In an alley behind an Austin gym,

Leo is a tall, spare man with graying hair to his waist —

a grizzled beard, strong eyes, and good hands.

The old psychic belly dancer is possibly Austin’s poorest roofer —

a Kansan, his mother died when he was ten.

Leo attended Kansas State, majored in pussy, served in Vietnam.

Acting upright in a business of grime,

he converts the risk of the street into cover.

His father, Raymond, hauls the trash and tracks our hours.

Rafael’s the jefé with a hot tar mop,

leading the Spanish/English speaking crew

after eighteen years on the mop — he almost never speaks to Leo.

The tar paper and nails

are mostly put down in the heat

by Baroul, Castro, Smiley, Camey, and Rico,

Dr. Brian, Uwe, and Steve. And there is one more man

on the hoist that everyone must adjust to:

Leo’s night watchman,

tracking the homeless up and down the alley;

James is a damaged black man

living in a shanty on the roof of the gym —

maybe a prison man, maybe not.

The hot tar life is for the people outside of things.

Our comedy begins at first light,

starting awful trucks parked behind the gym;

opening sheds, pulling tools from them; loading trucks —

a simple thing complicated by our intelligence.

Leo interferes and changes much of what is done

by the gang of men untangling extension cords

or straining, shouldering rolls of modified paper.

In the truck, room is made

for John Joe Monroe if he shows.

Raymond watches; Leo shouts;

Spanish humor; starters grind; the sun rises more;

trucks start or they don’t; trees smile if trees do.

Mornings are best.

We head down the alley,

a dirty soap river speckled with tar pieces

and shingle fragments,

populated on its banks by homeless men.

Broken gas gauges on the trucks

suggest a stop up the street

at the gas station for Celia’s coffee.

Dirty men unpiling from dirty trucks,

waiting in line with pristine secretaries for coffee.

Dr. Brian studies physics and takes creative writing.

Young Steve wants to be a writer,

though his typewriter doesn’t return.

Uwe, the German, has an interest in

Hispanic women and makes fine shoes.

Pouring the rest of the crew’s coffee,

Celia ignores John Joe Monroe’s language as racist,

sexist, Harley truck beer nonsense at its best —

mindless babble the rest of the time.

Morning continues.

On the drive to the roof,

Leo’s junk engines run on loosened coil wires,

and starters hang by their threads.

We arrive; more unpiling and shouting,

backing and filling; work starts, and Leo leaves for collections

exhausted — from starting James on the hoist.

James violently exercises the rope.

Rafael’s crew enjoy the work, their humor gathers stamina.

On hot tar roofs, I’m the mule carrying hot tar buckets

hoisted from the kettle by James to Rafael on the mop.

Castro runs the kettle, and the tar releases sulfur

as it boils in the squat, evil-looking furnace on wheels,

sheathed with overflow from countless jobs.

And there’s a stench of heated hanging tar.

Its seething roil will take your face,

demanding a protocol in its care.

A deliberate haul and declaration,

so people know where the hot tar is.

A seven-foot pole mop holds fifty pounds of tar,

resting in a heavy cart that Rafael wheels about the roof —

lifting the mop against five hundred degrees

of plastic resistance;

lifting and sealing over and again;

taking years off his life for hot tar money —

a soldier of hot tar.

Rafael’s crew is smooth —

moving mechanically raises our risk; tar requires rhythm.

Baroul does all the little things well, using the kindest tone.

Rico rolls the paper and cuts it for the geography —

always moving so as not to scorch his feet.

Smiley does the metal perimeter,

anchoring the roof profusely.

Camey smears plastic, entombing the fixtures

while his face heals — injured in a fall through a roof —

his bones’ knitting helped by last night’s beer.

The kettle burned Castro’s hands

when he slipped loading a keg of tar;

working carefully now, his hands swathed;

next week he visits his young daughters in Tampico.

Work moves on in three-foot bands,

back and forth, often triple layers of paper and tar.

Unseen from below — a nameless succession of roofs,

tar stench, and heat cooled slightly by humor.

The work is its own — remove,

haul away, restore, seal … heat all week.

Return evenings to the narrow alley,

which is hard to maneuver in,

as the entire crew manhandles the kettle

into its shed — settling into its berth against the gym —

a pain in the ass as we unload everything:

stuffing, pushing, twisting ladders;

abusing tools, equipment, ourselves.

Light shines brightest then.

With greasy ledgers spread open about an office in the alley

on the trunk lid of a dead, brown Cadillac.

We turn from the hot tar life to Raymond

enthroned on an upside-down garbage can —

piles of cash for each man on the trunk lid,

weighted with cold tar pieces.

Look at the hours and the draws; pay the man his money;

pay for the tearing, the hauling, and the hot dance with the mop.

Leo hands out the money, and we leave till Monday.

The alley is quiet except for tired homeless men …