![]()

Ten hours north of Austin,

I slept by an Arkansas cotton field.

At dawn a tractor working down ends woke me.

Couple of hours down the road,

a guy had a yard full of motorcycle frames.

My Water Buffalo’s chain was worn;

but the owner said the Devil Rays had taken his,

so my journey went on.

After sundown, a wide gray river came into view —

the Arkansas was dark water large,

and I paused to roll a few Drums.

Back on the bike, I crossed the river valley —

moonlight and wind — smoking Drums

one after another behind my hand.

My plan was to stop in Kansas and see my children,

but their mother told me

they were in Fresno for another week or so.

Rebekah also said my mother was still in intensive care.

At sunrise, I slept for an hour behind a hay stand.

Entering Missouri’s Bootheel by midday;

I crossed the Mississippi into Cairo, Illinois, by late afternoon.

Then east into a triangular region called Little Egypt.

Turning north, the rest of my evening became a swampland

past random shacks and a Golconda roadhouse.

I turned around for a beer.

Inside, regulars below the levee

said they did floodplain chores for beer;

and I drank a few, writing about Devil Rays and farm dreams.

After the bar closed, I slept on some straw bales.

Packing up under full sun,

I rode north on the Coal Road —

as lower Illinois rose and fell for forty miles.

Asphalt shimmered in afternoon heat,

dividing early corn from dry yellow grain.

I parked by the grain and walked in.

It waved on my way through, and the wheat looked ready.

Across the road, corn rustled, too.

Starting the bike, I threw the chain putting it into gear —

swore at myself and began walking north.

The Coal Road ran into a wilderness

of tangled oaks and vines, until a woman

in an old GMC passed … slowed … backed up.

Was that my motorcycle back there?

It was, and I told her its chain was undone.— “Get in.”

She had some — a good-looking woman like my wife,

in overalls with a baseball cap over chestnut hair.

Her truck muttered past rotting barns, rusting combines,

and shady forest around small, greasy lakes:

they were abandoned pits filled with black water.

She’d grown up around the holes and shacks.

The Coal Road led to a hardware store,

followed by a small grain elevator against railroad tracks.

Turning in where the sign said Amish Grain,

augers were pouring old crop down into a waiting train.

Parking next to a wooden shed, she went inside,

returning with parts for 80 chain.

I thanked her and asked her who she was.

She told me her name was Esther Watson

and that she was partnered in the elevator with the Amish.

Prior to Austin, I’d been married to a Mennonite;

had two children; and I was on the way there.

After another mile, Esther asked about my marriage.

“Well, Rebekah was a Kansas Mennonite,

who moved out to California to break up large farms.

Our children were Helen and Moses.”

Esther glanced at the mirror,

passing wilderness and familiar wheat and corn,

till the oily gray Buffalo was a half mile away.

She parked; we both got out to mend its chain.

Were my folks around? — I said my mother

had lung cancer in Fresno.

Had I seen her? — Last year.

She clipped the links and stepped back,

wiping her hands with a rag;

then gravely nodded good-bye and got in the cab.

Pushed the starter switch, but nothing happened.

Raising the hood, we found a loose coil wire.

I reattached it while Esther said her harvest started soon.

They could use me at the elevator,

and there was her ruin to sleep in, too.

So I followed her battered truck

down the Coal Road, crossing bottom land

and trees till we turned up a grassy slope.

Her hilltop house and grounds were a simple affair:

tethered goats called “Jack and Jill” quietly

cropped the grass around her rock house;

black oaks shaded its rough metal roof and wide porch.

The ruin was a stone barn overflowing with grimed engines

and tools; farm pits and old coal pits completed the view.

After putting my gear inside her barn,

we sat briefly outdoors at a table under a tall arbor

of wild roses sprawled across rusty yellow-flaked motors.

Those were Amish farms below — at least the first two were

and most of those engines pumped out the shaft

mines before they switched to pits.

She stood up and said she’d let me know

when it was dinnertime. A couple hours passed,

then she called out the table was laid.

Over soup I learned Esther was a widow

whose husband had restored turn-of-the-century engines

for museums around the world.

Thomas had been gone a few years;

so we kept on talking about his aging engines

over beer and stew, till she said

goodnight and left with the dishes.

Jack and Jill watched me all the way back to their barn.

The interior was gray stone and open, aging doors.

Night sounds and moonlight

lulled me to sleep next to iron shadows.

In the morning Esther brought coffee —

we drank it between an old reaper

and a mine pumper with a huge piston.

How come the open pits were closed? — Dirty coal.

Had the Buffalo always been mine?— No,

I’d traded a rain machine for it.

Did the bike ever go fast? — No,

Noah set it for slow.

The next few days she had me

thinning oak trees until the harvest began.

My job at the Grain became unloading wagons

driven by teenage girls, whose wagons

were combinations of farm wheels and red barn siding

strapped with leather harnesses.

Esther kept her distance through the first part

of the wheat harvest. Amish horses did too,

while the elders taught me quite a bit of profanity.

And my own desert farming

was handled like a different sect.

Harvest sandwiches were made by Amish girls,

who looked with direct blue eyes and liked my beard,

while I enjoyed holding their mules.

Six days into the harvest, the younger Amish

crowd invited us to a gathering; so Esther

prepared me before sundown: The Amish protocols

had the men buy beer, then wait for women

while drinking in front of the hardware store.

Young women would leave home in smocks,

change to jeans. Everyone gathered

where the horses and buggies are hitched.

After beer, couples spun off through the fields

toward the old coal pits —

they’ll sleep together in the woman’s home

and have breakfast with her family before going to church.

The congregation watches over the protocol:

Doing it twice leads to a proposal.

We rode the motorcycle there;

drank a lot of Amish beer; rode home;

and said goodnight at two in the morning.

Alone in the barn on the cool floor by the motorcycle,

the roof was mounted on hand-hewn rafters —

they were heavy, close-grained, on their third building or so.

Illinois days had dusty wagons and gathering clouds at dusk;

but the succession of thunderstorms left us alone,

while we made a better rack for the Buffalo

and attached a hydraulic hose to a sprinkler on a ground slide.

We’d just started the Rain Bird

when she told me: Thomas got crushed under an engine,

and his ashes were scattered there.

I wondered when. — Not long before … she was forty-one.

Our evenings were spent watching her Rain Bird,

trading grassland for desert stories under leafy trees.

Mornings, Esther wore nightgowns on her porch,

watering vines in the see-through.

Another week of horse-drawn combines

finishing final fields and left unhitched on the turnrows.

Amish plows turning the old crop in.

And Esther came out to the ruined barn to ask for another ride.

We rolled south past an old tornado swath,

with circling hawks nearing the river.

And along the Ohio, we watched a barge

barely make headway.

On our way back, we stopped at a country store,

bought a couple of beers, adding up my wages

with a couple of more. On the way out the door, she asked

what had happened before Austin.

I said, “Working a movie on Jack Ruby.”

Then we rode home through darkening vine tangle

and farms, till we parked by the barn,

where Esther asked me to wait while she went into her house.

Coming back with a small journal,

she opened it to a sentence about augered grain —

it was good, and I told her so.

But all she did was whisper

the cash in the journal was mine …

leaving me alone with muted colors in the dark,

except for a garden hose curving toward a Rain Bird.

After opening its valve, my return to writing

began with wet circles on the grass.

Then I packed my gear and rolled my bike

down to the Coal Road, which had taller corn

by gray-yellow stubble.

My Kansas children were a day away;

the road shimmer was in hiatus going over the rise …

Humid summer changed to dry heat toward Wichita,

then to rolling plains where the corn was blue.

I rode past several herds of Kansas cattle

and green tractors in the fields.

Rebekah had said to turn at Asphalt Cross,

count for ten miles of rural road, and their new home

crested a hill as a half-cylinder hut covered in bramble vines.

I parked the Water Buffalo in the pasture behind her house;

found a rock tank for domestic water

and cottonwoods to shelter my campsite.

The summer school wasn’t too far, and the principal recognized me.

Helen and Moses broke from class and we met in the gym.

They called me a ragged beard,

and I was pleased by the way they’d both grown.

We shot a basketball; and my son, Moses,

had a future in the game, since his shots always went in.

Helen said she was writing summer school essays:

I had confidence in them — because I needed to.

Moses rode home on the back of the motorcycle.

Passing the farms, their neighbors

were squared-off faces with dust in their lines,

and their ideas resided in Mason jars —

like ethics captured in season.

Moses said he’d been raised on the hard clay.

That night, Rebekah’s interior meant curving walls

and old objects from my past continuing to surprise me —

scratched tables and plates, an upright piano, and so on.

I called the ranch, and found out Mom was home again.

The second evening, the children got into marital allowances,

which were remembered as twelve dollars a week.

I’d spent mine for coffee and cigarettes;

Rebekah saved hers to buy the piano.

Over the next few days,

their routine left me with time on my hands,

so I kept workin’ on a farm dream.

After dinner, Helen joined me, camped in the pasture.

Both of us were folded into a pair of green-red chairs.

Helen showed me a ten-year-old Polaroid

of herself and Moses reaching up for plates of cake:

me leaning down, my face was opaque …

theirs were six and three, streaming light from smiles.

While poking pieces in the fire, our evening faded —

Helen worried about what the settlements say,

even though I looked the same. I was divorced from her

mother long before the men’s shelter.

Was I treated well?

— I said I was.

And where they’re concerned?

— I nod in their pasture, and say I am.

We let the fire crack through the dusk change;

her horse stood outside the light, and a cat slept under my chair.

Helen asked if I ever dreamed.

“Not often, except maybe the basketball dream.”

“What happens?”

“Ball always comes on the right side of the court;

I jump to shoot; shoot and keep rising — it’s an awkward feeling

through the roof, then I lose my fear, and awake in outer space.”

“Does your shot go in?”

“I can’t say that it does.”

“Are there other dreams?”

“Well, I’m chasing Moses in a farm dream.”

“Is there music?”

“He hasn’t finished it yet.”

Then Helen told me about her own strange dream.

I asked, “What kind?”

“Well, I dreamed about the stump over there when it was a tree.”

“Not the seedlings?”

“No, just the tree that I’d never seen.”

I got up, and looked at the stump in the firelight,

again at my daughter; then I counted the tree rings

after Helen asked me to count them.

A night owl screeched overhead through the counting.

“My dream was a hundred years ago.”

“What, Helen?”

“I dreamed about a prairie woman when this was still grassland.”

“Did you need her?”

“I don’t really know if I needed her or why she came here.”

“Is your dream alive?”

“It’s after I’m gone.”

“You’ve gone away?”

“I’ve gone away, but I’m buried under the tree.

And how do you get a tree on natural grass?”

I left the stump, and sat in the chair, and asked,

“It’s a conversation under the tree?”

“Kind of.”

“You and the dream?”

“Yes.”

She turned to the complicated rock tank

with the green black algae line

running crooked to the seedlings.

I nodded for progress.

“It’s the sunburned prairie, Dad: Some of those stones

were hauled to the hillside spring to make a well.

Their work was a rough construction,

and a little water ran off — a slow constant seepage —

and the woman needed a tree; so she planted a seedling

and then channeled the leakage.”

“Helen, this is happening on the prairie?”

“Here on the Great Plains.”

“Was the woman alone?”

“Until she married.”

“Was she pleased?”

“Doesn’t matter — the woman was me and I survived my husband.”

“Who was he?”

“Just a man that went away.”

“Like me?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Weren’t you lonely?”

“No. Moses stayed with me as a quiet man at home

till I died as an old woman with my tree in full view.

I’d planted it when I was thirty-one.”

“Was the tree big?”

“Tree’s huge, but my dream had Moses digging my hole.”

I looked suspiciously toward the stump.

“Where does he do this?”

“On the house side. Moses broke our saws on the roots

and dug all the rest of the night with his hands smoothing the hole,

finished by dawn; he’d made the grave signaling my life.”

“You’re at rest in the shadow?”

“I’m facing my home.”

“Jesus! — did Moses stay there?”

“Yes, he remained as a large man climbing his boyhood tree.”

“What else did he do?”

“He watched congenial birds in the walnut branches and wrote

about them over the years, wondering if I felt his new work

or heard the birds. And we talked about our kind of lives —

and the others of sensitive crows and aggressive squirrels,

taking their habits from blue jays.”

“Are there green leaves?”

“Ash green — but Moses was in good weather and waiting for contact.”

“From you?”

“No, just contact like the scattered lights

from other homes, and cold stardust,

and crooked flow from the well.”

“Helen, does Moses live?”

“No, he died when a lightning strike killed the tree.”

“What follows?”

“I woke up. And the next day we wanted some shade,

so Mom dug the holes, then we mixed half shells and leaves.”

“Who placed these seedlings?”

“It took Moses all week.”

We sat quietly while the fire burned down.

My daughter returned to the hut and I kept glancing

from coals, to the tent, then over to the seedlings.

After a last nod, I crawled into my tent.

Moses woke me from a farm dream in the morning …

My son wasn’t around the desert town.

Light spilled from a doorless frame.

I stumbled in and out of the shadows into a ragged place.

The interior had ripped Sheetrock walls

lined with emaciated small men, sweating shoulder to shoulder —

with stick legs stretched towards the center of an aqua carpet.

Quiet men smoking opium, smelling raw, heavy, and inviting.

Each man’s smoke stayed down close —

no movement showed in the humid den.

I shook one, then slapped another, asking them about Moses;

then I shook and slapped them all, asking everyone.

But he wasn’t there, so I left the desert town.

An hour later in the dark, standing beside a road,

several thousand farmworkers went to separate fields.

I tried to join the one-way procession of old dusty sedans

followed by battered vans with gear piled and roped to roofs.

But I failed and stood outside the lights,

shouting at the caravan on the way to yesterday’s field.

Then Moses roared by in a melon truck.

I ran down the oiled road after hanging wires and crooked lights —

like a runner in the gaps between the future and the past.

The future kept moving away,

while the past kept coming up my back —

till I staggered to the borrow pit,

gasping at muddy undersides with hanging tailpipes

and stray fabric on the door bottoms.

After the hidden side of tires passed,

I wondered which patch Moses was in —

fell down on the road as light gathered

below layered clouds. Then dawn never really showed

on the kind of morning that usually began with a sunrise.

But Helen’s cat wailed

as my tent snapped and rattled in the Kansas wind.

It felt like wet sweating, sitting up for a cigarette,

ashing into a Drum can. Believing in old dreams

inside new dreams and smoke.

I fell back to sleep inside more dreams as a small boy:

Hot afternoon rides through the cotton

in a dusty four-door beige Chevrolet —

body odor mixed in with the smell of wet carpet,

from leaky dash-mounted air conditioners

and Viceroy cigarette smoke —

in a wilder country with more tumble than fallow.

My father had more land than water,

and his impact sprinklers smacked the cotton —

as concise Spanish rattled from sight-line radios,

using a long antenna bolted to the back bumper,

then latched to the front, over car roofs

so they wouldn’t tear off under bridges or in trees.

They gave and received on rough roads,

made brick hard from traffic

through the overthrow of sprinkler lines.

Spilling Cokes on the hot seats,

I napped on my back in the heat,

as the car swayed and turned through the fields

for twenty years — changing me to an older boy

inside a jarring sensation of circling through turbulent air,

before slamming down hard to a stop,

by reversing some turboprops on a white King Air.

Landing down below the ledge

of a sandy hill where the old tools lived,

the airplane’s door opened —

there was hidden-away evidence of wear

and changed minds by the sound

of our north well engines and the water rotation

of ten thousand Rain Birds.

Both sides of a dry wash

had mismatched cottonwoods —

a dusty sound in the breeze as they held on

for rolling colors of exposed profiles.

Whitened dry grass struggled across the wash

on some ground made in shades of brown.

The grass lifted, and my needs changed

to new straw walkers, in an unfamiliar heavy country

where solid lines of red tractors rested

on cracked clay from drought.

I was early — an hour before the farmers’ tools

were auctioned; and I hate an auction of that kind.

Needing new crankshafts, fruit chains, and straw walkers —

maybe they were lying around in the brisk morning sun.

But all the scrawny auctioneer offered

was acid coffee, a bad taste poured on the ground.

Then Helen’s anxious cat scratched again …

waking me to a dead bird in Kansas.

Accepting her strange mangled offering,

I fell back on my sleeping bag.

And then the images hardened

into black ice on the asphalt —

with Moses calling out from some wet weeds.

A car started spinning at me and blocked the road.

Flashes of round eyes — mine, theirs —

as I veered into the corn snow.

I slid to a stop in the greasy reeds;

got off shaken, kneeling in a cold field

in a low corner stand of hollow femurs.

Moses slapped me and stopped that dream …

After mailing everything to Luthor,

I left Kansas low on money;

ran into storm clouds near the Four Corners —

where a Baptist farmer needed his hay hidden from the bank.

I worked there a couple of months,

hauling it into his canyons and had about finished

when an irrigator answered a question

I hadn’t really asked him:

the answer came when I changed his water

in exchange for something to eat.

“Hey, Clifford, I can fix these ends

if you do the cooking tonight.”

“Hell yeah, Roy, I’m hungry and thirsty;

let’s eat by the blue chairs where the canyon winds rise.

I’ll take the tractor for groceries; the trucks have died.”

“That’d be swell, Clifford.”

He drove the Farmall to the store

while I straightened his sprinkler lines.

Clifford was paid to keep

the rolling wheel lines straight and defined.

An irrigator with woman problems, he ran from all of them.

Always smiling, watching his water

through the rolling pipes as the sprinklers

started at the far end cap and back pressured

to where he stood — holding the world harmless

while his wheel lines meandered.

For ten years he’d been a sous chef

along the Wilshire Boulevard —

he was a Ute Indian everywhere else.

Clifford Leamas did fine things with corned beef hash

and washed it down nightly with most of a case of beer.

We usually slept in a trailer between

the Four Corners Point and the town of Yellow Jacket.

Our friendship was based on the poetry in Clifford’s voice.

The last evening was spent in the southeast quadrant

under the Four Corners stars

as he prepared his generous hash

and a story about stashed and oily money.

“Roy?”

“Yeah.”

“You ever have any big money?”

“Sometimes.”

“Whaddya do with it?”

“I used it to grow cotton — how about you?”

“Mmm, yeeaaah, once I had a lot of money.”

“Did you do good?”

“Maybe, I think so.”

He poured a little wine into the hash,

started working the clams in, saying,

“I wish the stars were money.”

“Why?”

“‘Cause the stars rain down on those they love.”

“Have the stars done that for you, Clifford?”

“Yes, they rained down on me in L.A.

when I got drunk at Benny’s, too drunk to see.

It wasn’t too long ago —

and I ended up on a Wilshire bench;

sat there a while before this other guy joined me.

A tall, thin man wearing pants inside his boots.

We sat quietly on the bench ends, watching the street —

he first, then me, asleep. I woke up at dawn, day to come,

the city starting. Deliveries were being made,

busloads humming and going.

The tall thin man started up, too,

giving everything a nodding wide smile.

He left on the six a.m. downtown — we never spoke.

In about twenty minutes, a fog moved in, bringing a chill.

I saw that he’d forgotten his coat, an old green driller.”

Clifford’s stirring stopped when he asked,

“Roy, how much hash you want?”

“Lots.”

He returned to stirring, then glanced skyward:

“Roy, some of these stars are curling coming down.”

“A few, it’s busy tonight, I don’t know why.”

Our Four Corners night

was full of light shards from far away.

Infrequent streamers sailed over our heads,

crossing west over the mountains.

Shipping affection beyond our horizon, Clifford said.

He returned to his hash and story, saying,

“I carried that coat — a driller — with me up the street,

the moon lowered over the end of Wilshire

before the fog completely covered.

Sleep-cold and fog-chilled, I put it on as I walked away.”

“It smelled faintly of earth and maybe wine

and had sort of marks or arithmetic on one of the sleeves.”

“You always talk like this telling a story?”

“Every time, Roy — I’m a perfected Ute in a rhythm

under the full moon, and we’ve got chips in the sky

and a crackling fire to warm this hash.

We’ll eat it and wash it down with spirits.”

We ate gift hash together;

it was magnificent, chased with more beer;

bellies full, resting on smelly old recliners,

as galaxies susaned slowly overhead.

The sky seemed to close as I wondered

about Ute story traditions. Would Clifford follow this one,

or would he lazy back trailing this alone to his own horizon?

“Roy?”

“Mmm … ”

“Wearing that drab coat all through the weekend

made me feel good — loquacious is what I was.

Went all over town talking to folks,

like when I quit tending sheep

in North Dakota. Damn words just poured outta me.

Met this mystic Iranian film student from Montreal —

we talked most of Sunday about landed spirits …

whether they come from above or below.”

“Where do they come from?”

“It depends, Roy, the spirit water mostly from above.

Sometimes it travels the seams to where you live.

Larger forces control these things,

and they’re inside of memories.”

“Memories?”

“Yeah, memories are the stay-behinds

and spiritual lessons connecting time and life forms.”

“Come on, Mr. Leamas, what’s that mean?”

“Collections … recollections of aged hues

flowed on a rough raised surface or ocean-made winds,

wearing that mountain shape down to her base.”

Or me telling this story to you — a traveler — an event

happened far and away and told now.

We’re in a surveyed land, all right:

but you’re from somewhere,

and I’m from here — where these stars

are pretty constant teachers,

listeners, no matter who we are.”

“Okay, Clifford.”

“I kept talking to the film student.

She told me I was a beautiful man —

no one’s ever said that to me.”

“You surely are, Clifford.”

The story paused as he gazed

down at the fire, reshaping the embers.

The glow increased on the round-faced little man

with shaggy eyebrows and a missing tooth.

Clifford’s eyes warmed over the fire with affectionate film

running in his mind; his profile showed insight and confusion.

We both laid back and watched the sky breathe —

in the altitudes the cosmos is richer, fuller, and alive.

“Well anyway, Roy, I wore that coat through the weekend

and into work; hung it where the dishes get cleaned.

Everybody sliced, and tossed,

and sprinkled for the next three days.

I almost forgot the coat hung wet over the washing machines.

Hill fires were doused in the rains that week.

Pouring outside when I finished my shift,

so I reached for my damp coat, on the way out the door,

noticing a paper sticking out of the inside pocket.

I put the driller coat on going to Benny’s.

It was a loud rain, sheeting sails of rain.”

“Not bad, Clifford.”

“At Benny’s, I talked to the Strolling Bimbo

about horses a bit — mudders mostly.”

“Who?”

“She’s a woman likes to spend her time at the track —

owned a piece of a horse named Strolling Bimbo,

so we called her that.

I used to love her till I broke my leg,

feeling awkward about my cast and exposed toes —

she wasn’t a healing spirit, Roy.”

“Go on.”

“After the rain stopped,

she made me uncomfortable,

talking up a horse named Terror Orange.

Guess I drank some; then went outside for a walk —

head down walking right into that bench,

and I cracked my knee on the angel bone …

and fell off the yellow curb

on my face in the street. Got up on the bench,

and my knee was just growing:

It hurt like hell; I cried like a child with my nose running,

feeling sad and lonely.

I reached into the drab driller for a smoke —

don’t know why … I quit years before.

When I did, I found this package — bag-wrapped, solid,

but not too thick —

you’ve been afraid?”

“I am now, Clifford.”

“Well, I was scared, damn spooky;

white-light night-street; a forty-two-year-old Ute cook,

alone, childless; a gin-fooled lover of used women;

and my knee swoll up like a big tuna.”

“Are Utes afraid of writing?”

“Like snakes that fly: I’m a talkin’ Ute.”

“What about the package?”

“Ripped it open, and found forty-one $100 bills inside.

I sat there — shocked, stunned, like a newly shorn sheep

on a cold sellin’ day — just staring at the money.

My knee still hurt; so there’s no such thing as painless cash.

Lookin’ and feeling completely suspicious,

I limped off the Wilshire into safety

in the men’s stall at Benny’s.

Closed the door and thought it over, checkin’ it out —

there were lines drawn in the wrapping,

and between the lines were words.”

“What words?”

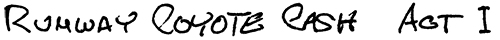

“Plea take this Runway Coyote Cash and go to Victorville.”

“Say it again?”

“Plea take this Runway Coyote Cash and go to Victorville.”

“What did you do?”

“Took the cash and stayed the hell away from Victorville.”

“All right, Clifford.”

He looked through me for a time;

got down by the fire out of the wind — it was warmer there.

“You know something … I sure feel you do.”

“Maybe I did — maybe again tonight, Clifford — keep going.”

“I left on the southern bus trails outta L.A.

The money weighed good and smelled sort of oily.

Gambled with it in the desert

and won some for the only time.

I kept it and bought an old Yamaha

for the ride to Colorado —

before camping up around Mancos,

in the Blind Horse Canyons.

Cold, so I wrapped up in that fatigued driller.

It also had marks on the sleeve that led me to believe

the money was part of a larger whole.

I made fires, and sweated, and swam. I didn’t think:

I pondered. After a week, I went to the reservation

to see my grandmother —

she’d raised my sister alone — I told her some of it.

She doesn’t know about my life,

she feels it; so I gave her the money to use.”

“How’d that work out?”

“I did good: My sister traveled on some of the money;

now she lives in Moab and paints elders

smoking around fires. You’d enjoy Linda, too, Roy.”

“I’m glad to hear that.”

Listening to the molten coals quietly settle,

our night canopy rained old time through us.

Clifford watched me get up and wander

over to the canyon edge. I gazed across

the moon-yellowed abyss; couldn’t see anybody

or anything and leaned out over it.

The wind took my hat straight up — all ways.

The upwind brought changed sound from far away,

maybe long ago. I was just about complete … aired out,

leaned back, and returned to the fire.

Clifford stretched supine on the ground near the heat.

In the still, that unusual wind — a foot over his head.

I gathered and settled also; then we just peered

at each other, and opened two more beers,

and studied them … but they didn’t teach us much.

“You know, Clifford, this fire’s almost done —

those white ashes remind me, looks like driller’s paste.

Driller’s mud partly comes from ground-up money.

I’ve heard our Treasury Department

grinds up the cash and sells it

as a constituent product to manufacturers.

A guy named Gino buys some

and makes Gino’s Well-Driller’s Mud.

Gino’s mud saves wear on the well-driller bits

and cleans their well walls, even on the deep holes —

according to a Polish stand-up bass player

and well-driller’s son.”

We studied our beer a little more till Clifford asked,

“Do you know something about this? I feel that you do.”

“Something — yeah, a lot, I do — but it’s okay.

You told it right, and a fine thing came out of the transfer.”

“Roy, why are you here hiding hay from the bank?

Do you come from things, are you going back,

or are you running? What, Roy?”

“My mother is dying in Fresno.”

“Will you be on time?”

“I’ll try.”

“Aren’t you in pain?”

“No, I’m just hiding alfalfa while my life cures out of sight.”

“Go on, Roy.”

“We’re here thinking of what you called ‘stay-behinds’ —

both thinking the other guy feels their memories are weird,

both knowing they aren’t, Clifford.”

“That’s no answer.”

“No, it’s not — but what’s this coat about, this driller thing?”

“Hell if I know — I just liked the word.”

“Where you got it?”

Clifford went to the trailer and returned

with an old, ragged, oil-stained fatigue jacket.

I held it close and looked it over. It smelled of grayed sweat,

distant earth, and red wine, with a fresh overlay of beer.

“Did you say the man on the bench smiled?”

“Yeah, almost a headshake grin.”

“How much did you win?”

“Almost $15,000.”

I looked up at the chips in the wheel sky.

“Noah Ingram left that cash on the bench,

Clifford. Noah did that.”

“How do you know?”

“As a boy I became friends with a marine.”

“Where?”

“Noah was in between Asian combat tours,

working in a summer boy’s camp

when he taught me to high jump —

before returning to Indochina and the wars,

which almost destroyed him.

Asia used up his humor and his God —

and made him afraid of memories or the stay-behinds.”

“What was he like?”

“A loner — I never completely understood

— a really sad, killed person.Sometimes

he’s a metal sculptor in a place called Devil’s Den,

and he’ll spend the fall in the winery crush as an oiler.

Noah calls wages ‘Runway Coyote Cash.’

When you said headshake grin, that meant ‘Noah Ingram.’”

“I’m a drunk Ute outta the wind, Roy, running from wives,

ex-wives, and girlfriends. I’ve always thought beer

or uneven sprinklers, except when I see

across the hollow land. Noah had that look —

maybe he could see that far,

maybe he’s right for it … I’m not.

It’s usually a pain in the ass.

My grandmother’s that way: sees fields and events,

sort of. I got some of that from her,

but it adds up to ‘screw up’ with me.”

“Maybe, maybe not — you didn’t lose the coat,

not see it, or give it to the beer fairies.”

“Why, aren’t you surprised, Roy?”

“Noah could have been building guilt on the rundown …

ready to unload. Maybe you just had a good face —

you do, you got one. And I guess

he slept with you on the bench,

maybe thinking you’d perform all right.

Whatever. He left the coat with the money.

There’s not much accidental about this —

that motorcycle I ride was his.”

“Why runway coyote cash?”

“He was kind of a medic on the Laotian Plain of Jars,

where ashes and old teeth

are memorialized in clay containers.

He used to have a clay jar, ash full

with a couple of old teeth settled in it.

He could have given you that —

instead, he gave out wandering cash

and something for you to do.

So you got some of both, Clifford.”

“You’re talkin’ strange teeth from Asian plains —

you going back to any truth?”

“It’s diminishing.”

“The sleeve?”

“I’m getting tired.”

“The sleeve, Roy?”

“Those marks list the things he may have wanted to do.

My guess is he might have just meant

to confuse you with the Victorville.

He probably hoped a good thing would happen.

It did: a restart for you, and your sister is painting in Moab.”

Clifford rearranged the fire while I looked behind me

and reached for a stone and put it by the fire ring

in the southeast quadrant; his eyes expanded.

“You know from who about marking stories with stones?”

“Noah … others.”

He nodded, and then again, when I wondered,

“Clifford, can you ask your sister

to paint a smiling man by a stone-ringed fire for me?”

“Sure, Roy, I’ll tell Linda when it’s aged and right.

I know you’re leaving soon, but you come back when you can.

And when you do, you check by the reservation or Moab.”

Our sky lightened

as the stars faded. It was almost a windless time

for the dawn water changes. I’d hidden all the hay

from the farmer’s creditors. Couldn’t find my hat.

I hope to see Clifford Leamas again; and when I do,

I’ll tell him whatever I learned about Noah Ingram.

Maybe get my hat back …

My mother was almost gone that fall,

when a place called Mule Hollow

took my motorcycle over the edge.

My wreckage got sold to a Durango Mormon.

Then a Mormon couple hired me as their evening dishwasher,

between forklift days stacking in a warehouse

and late nights sleeping in a radio station.

Needing transportation, I bought another hat

and walked to the edge of Durango.

Right away, Alvin saw me on the side of the road

and gave me a ride over the Wolf Creek Pass,

to another faded Water Buffalo in Guymon, Oklahoma.

Agreeing to buy Alvin’s motorcycle,

I paid it off driving a corn truck in Liberal, Kansas,

for a struggling grower who was maimed and broken by debt —

and kept farming from his crutches.

Back in Guymon once more,

Alvin’s documents were delayed,

which got me drinking beer in a bar.

Off to the side, a few sleeveless guys,

shooting stripes and solids,

kept going back and forth to the bathroom for cocaine.

They laughed at me as an Amish biker

in a place where it’s “What’s wrong with you?”

Should have just paid the goddamned tab;

instead, said I’d farmed in California

before doing a little writing and buying Alvin’s motorcycle.

They backed me into a corner

and called me an “undercover asshole.”

I bounced a blue ball off a guy’s head

and left the Panhandle on the second Buffalo with dangerous tags.

Ball bounced kind of wrong in Guymon.

The second Buffalo ran well in the dark into Kansas.

After Helen and Moses beat me at cards at midnight,

my father called and told me about my mother’s coma.

I abandoned my children at noon.

The first hundred miles were clear skies,

till towering clouds arranged wind and snow

on the eight hundred miles to Flagstaff.

Coming down from the mountains,

my right-hand exhaust loosened

on a long, rough, gravel road —

and the weather warmed in the desert.

An hour later, along the Highway 10,

truck mechanics made straps to seal the cracks.

Furthermore, John, my attorney,

paid the bill and took me to lunch

at the Café of Both Marias.

A few hours later, I was tired …

fueled, and repaired across the Mojave.

A strap snapped, and I lost the whole

pipe — end over end — on another gravel road.

Climbing out of the desert into the mountains;

then back down into Bakersfield.

Explosive engine noise rebounding off the overpasses;

right-side flames singeing my clothes

through the bitter night fog to the Fresno closing.

My father stepped out of the room where his father died,

saying my mother didn’t have much of a future.

She died hour after hour, just past midnight —

on their forty-second anniversary.

A few whiskey bottles and nights passed,

before we gathered by the hole in the ground —

a family around a mother of eight, with one dead and one away.

Filling in the grave, I recalled

my mother and sister on softly curving rides —

year after year, ride after ride, across sunlit afternoons

water runs, cattle shacks, and shady trees — as the hole got filled …

So he got an all-night ride

through a voluntary jail and hot tar crew;

then across the prairies and over the mountains

toward the death of my source.

By sunrise, I’d told Luthor about Noah

giving money to strangers.

Concerned, the poet wanted to find the reason why —

asking me to stay while he did: therefore Luthor was away.

While he was gone,

my writing went on as morning black down low to gray

reminded me of Noah helping Luthor read my tea leaves —

saying I was gonna hurt someone;

which worried and pissed me off for quite a while.

But I’d been careful all along, because

I didn’t want to hurt anyone.

Even though Luthor believed Noah might have been

onto something — just got his verb wrong …

The “Cheney Spoken” began on a shopping bag

with a series of sprinkler lines as late fall turned crisp and cold.

The revisions were mostly done at night around an open fire.

Luthor’s landlady, Rena, always called out from next door to

lower the fire, or I’d be trapped in burning bamboo.

But my revisions went on till the dry cold turned to warm afternoon.

Word-tired and restless, my writing stopped, and I could hear

Rena through the fence, swearing at her weeds.

“Rena?”

“Who’s there?”

“Roy.”

“Roy, who?”

“From Luthor’s.”

“So?”

“I’m going up by the dam to look for words and language —

you want to come with me on the motorcycle, Rena?”

“Which dam?”

“The north one.”

“All right.”

I waited while Rena changed. When she arrived,

I told her it was a motorcycle.

“I wanna wear the fuckin’ dress.”

“Okay, Rena.”

We rode out of town, quietly heading north on the 41

as sunset darkened the roses in front of Marilyn’s vineyard.

We didn’t speak, we just rode.

I didn’t know her well.

She’d suffered mountains of abuse,

sometimes revisiting them.

A green-eyed blonde, wearing a

canvas brown dress,

she worked as a registered nurse

at the woman’s prison in Chowchilla.

She smelled of sage smoke and sweat.

I was poor.

The motorcycle had loud, straight car pipes —

Rena liked that.

We turned at the sawed-off mountain

and came to Rafchieller’s abandoned feedlot

on our right side.

Rena commented on the empty pens,

wondered where the cows were.

I told her Raymond hated cows;

shut it down when the market dropped.

He’s living with his boyfriend in Three Rivers now.

As the dusk went away

we stopped and walked into pistachio groves,

as she told me things about herself … others.

She’d married young; she had a son, a good one;

he wanted to be an artist.

Her ex-husband worked in a prison —

the real kind.

But she never loved him.

“Do you love pistachios, Rena?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Well, they’re pretty late around here —

another month till they split open. Let’s climb to the top.

Dr. Wills’s hill doesn’t produce as well, but the nuts are better.”

“Who’s hill?”

“Dr. Wills was a wealthy gynecologist and really big farmer.

He exceeded his dreams and his partners.

Two hundred limited doctors own this land, Rena:

fifteen cents on the dollar.”

“To hell with doctors, Roy — look on down there.”

From the high ground at night above four miles of pistachios,

you could look up to the dam — backlit, white-flowing —

or downstream, moving water banked by other groves

and hayfields mostly. We carried our stolen nuts away.

Then she wanted to go in to the town of Millerton.

We couldn’t — there’s eighty feet of water over it.

I did show her the old courthouse and the graveyard.

“They moved those before they built the dam, Rena.

The old town and houses are under the lake.

Once in a while, something comes up, but it usually stays down.”

It was in the old graveyard

that she mentioned Thailand and her plans to go back.

“I want to make scents for my living —

It’s why I’ve got those woodstoves plumbed over my balcony.

I do my trials and burn things there.

I’ll go back to Thailand and buy my materials raw;

I’m saving my money to go.

I stay away from people — except my son — at least I try to.

The prison work is hard for me,

and the women are just awfully goddamned vicious.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, they’re tired and ugly — even the beauties.

The whining, the gossip: it’s pretty sad and depressing.

I could show you one day if you want.”

“No, I’ll leave those women alone, Rena.”

Then walking into the cemetery, I asked about her husband.

“Danny was a prison guard. I left after a long whore of a marriage.”

“I’m sorry it didn’t go.”

“It’s over, Roy — he’s dead now.”

Inside the silent graveyard under dark oak trees,

I told her about an old black rainfall woman

who’d called cemeteries “stick bone places.”

Rena shivered, and then a little later

said she used to blow Danny

on the grass in the middle of Fresno Street.

“Are you living better now?”

She kissed me.

Rena was extremely graceful in the gravestones,

whispering “Aqua Bernal 1888 to 1933.”

Quietly wished her well in the gray monuments.

With great care and attention we read more names —

Burford, Mathieson, Blasingame, Walls — all buried once and again.

The last was Otis Diefenbach.

We went on with the ride,

going along the old flume right-of-way

and across the river valley.

“Let’s go on a little higher, take the 29 Mile Road.

There’s a saloon up by the Bass cutoff —

you want to stop for a beer?”

“I feel like shaking this hair out.

I’ll buy, Roy. That’s Dick’s Bar — have you drunk there?”

“No, I just heard about it.”

Riding together through air warmed twice by thermals

as the road crossed creeks,

she enjoyed having a good night, untethered,

and tapped me on the shoulder, saying she needed to pee.

So we stopped and peed in unison:

me over a ledge, Rena beside — squatting, giggling,

thighs shaking, gorgeous for a time. We left.

I liked her.

Up at the end of the 29 Mile Road,

a cheap motel glowed across from Dick’s —

which seemed safer

since his frontage was crammed with Harleys.

I didn’t want my second Buffalo destroyed

and didn’t much like Harleys either.

Then parking in the courtyard,

a raccoon fell hard off a trash can —

so we left her as guard over the bike.

Crossing the street, Dick’s windows showed grime flakes.

We heard filtered noise, and it looked thick hot in there.

Outside on the blacktop, we talked about my marriage:

“I was, Rena … not anymore.

Married a fine woman, and learned things too —

Rebekah, she was a political activist.”

“How so?”

“She came out here to break up large farms.

I was opposed — it’s how we met.

It’s all gone now; and I’m glad we married.”

“That’s all?”

“Aren’t you thirsty, Rena?”

We went into Dick’s cauldron bar where

the bartender’s name was Rose Anna from South Africa.

“I’ll watch those helmets here under my bar,

and wipe the bugs, too.”

“Not tonight Rose Anna, but thank you.”

Rena ordered a pitcher, grinning at my raised eyebrows.

“You can’t drink Guinness?”

“Well, once when I wrote a piece for Guinness,

they drank most of the stout.”

The music was good, some money-guns thing.

“It’s about this kid, Roy:

Goes to Cuba … gets in with the Commies

and stuff … in over his head. Calls dad for help —

send money, guns, and lawyers.

It’s the main thing of the song.”

She poured.

“Drink up, Roy.”

We drank, drank more, talked a lot, listened to “Soldier Boy.”

Rena said she’d played volleyball on the B team

while her father wrote $10,000 checks to strangers —

the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

She nursed and loved him for five years …

five years of brain strands slowly clouding and dying.

Her mother ran off with another guy,

because he was a good provider like her dad.

Rena met Danny about then:

a good-looking, bitter man; maybe a hitter.

She was like a lot of women born in the early fifties —

raised one way, for men, so to speak.

The world diminished the men, and the velocity scours the Dannys;

so the Renas make their own way with almost grown sons.

And the time was passing on.

Music was still pulsing in the loud smoky room.

Rose Anna brought us another glistening Guinness pitcher —

I liked Rose Anna.

Rena asked what was I writing.

“A farm piece about where sprinklers come from.”

“Luthor says, you’ve written about what you’ve seen or heard.”

“Maybe so, another journey

would be good, Rena — I need the distance.”

“Why, are you chased?”

“No, but the farming’s weakened —

we’ve matured so badly in the ‘One Man, One Vote’

and our ethics have gone to hell.”

Dick’s Bar was jammed all around us —

a raucous narrow place with big, open doors on the ends.

The long bar on one side was a bedlam herd of grazing, loud drunks.

On the other were scarred, uneven pool tables, full of people —

mostly pretense playing, ass gazing, and hustle stroking.

Rena liked the pool hall and bar. Combined,

it felt close and familiar; and her eyes warmed in the heat.

We lost three games. Then she began blazing, running hot tables.

An unruly mountain booze-and-speed crowd gathered.

Money was coming in, and I wanted to get the hell away.

“Can’t manage the crazies; we’re in the working Sierra.

See all the colors? I’d just get my head kicked in.

This is a mountain bar in a hell country of miscues and misfits, Rena.”

So we moved off down where the drinks were made,

by the loudest group shouting under the ceiling’s greasy fan:

Four or five men — stupid, drunk, throwing insults at Rose Anna.

A night crowd from the dam, with red, wet eyes —

staring at the hair under her armpits, and then through her dress.

They hadn’t slept in a week, substances keeping them awake.

So we left; and on the way outdoors, Rena asked if I ever knew them.

“No, they’re just searching

through those deep hell tunnels for water flow.”

Then while crossing to the Buffalo

she wondered if I was being sly about the cheap motel.

“Maybe so, it’s a long walk home.”

Then back at the bike, the raccoon

had completely chewed my seat to foam.

I accidentally hit the kill switch,

and the motorcycle wouldn’t start till I switched it on.

Rolling downslope into second and go,

we noticed the pistachios were missing —

raccoons have balls.

Our beer haze lightened,

coming down out of the mountains

with a night wind blowing against us

into the average blackeye country.

Blackeyes were beans, as rabbits quickly crossed our headlight,

and Rena showed the way along Bandoni’s canal —

which curved and coursed to a Whitney rise.

Below us, we could see the prison for women

on the east side of Chowchilla. I parked to restart.

She straddled my seat while

I laid in the dry cattle grass and wind,

listening to hard-woman Rena stories —

also about bitch convicts demanding to see the nurse.

I imagined confined women’s pasty faces,

sleeping twins with yanked hair.

I guess the darkness was moving to twilight,

so I told her a story about a huge, hairy man:

a young heart surgeon who developed a new procedure —

a saving one, he hoped.

Twelve terminal people died using it;

he’d operate, and they’d die.

Then there were two small children:

The first, a boy, just faded.

The doctor — almost shattered —

cried after he told the young boy’s parents.

He canceled the surgery for the second

child — a girl — and he went home to his wife,

who took him fishing, cradled him in a small boat.

A large, brilliant, crying man — a husk — he grieved,

cried more with her, and hated medicine and surgery.

“Good Christ, what happened, Roy?”

“The wife — you’re a nurse — she got him to go back.

The procedure was flawed only in its timing: they corrected that —

the girl lived. It’s part of heart surgery now.”

“Where was the doctor from?”

“The man was from Minnesota.”

More stories carried us from the dawn

into sunrise over the Chowchilla Woman’s Prison.

Then on our way through the hills,

a storm was building while I was musing —

maybe Rena, too — about the words,

White River flowing sprinkler ground,

rainfall black woman, Rena’s prison,

… the real kind — as we beat the weather home,

and we closed each other’s doors …

An hour west of Fresno

the Cheney Pump Station,

rose from an elbow plain on the oil line

from Bakersfield to east Bay —

a stark green-metal pump house,

with opaque, wired windows and a tall,

cable-braced smokestack.Inside was the oil pumper,

a loud reciprocating stationary engine

like the sister-ship engine to the south

twenty miles at Halfway House.

Someone needed to live out there watching things,

so the local oil company hired Dave Cheney

to manage the engine and pumps.

Sometimes Dave would get drunk

and heave off his legs to show the kids his stumps.

By 1947 an arid rabbit run

surrounded the pump station for several miles.

Then as postwar deep-well cotton approached the mountains,

my parents married and bought

some of the elbow plain and leased the rest.

Everyone called it “the Cheney Ranch” —

even Dave up at the oil-line pumps.

My parents built a flat shack next to a Hindu camp —

that shack still exists, leaning from the south wind.

Early on the land was slipshod surveyed

by Irvins and Woodrows.

They ripped it with yellow chisels;

then dragged landplanes across it to smooth.

Dusty truck odometers laid out boundary roads

for electric power arriving through wires on creosote poles —

legally wonderful poles for thirty years,

till that pain in the ass Louis the Bra sued,

forcing everyone to backslide and correct their origins.

It’s why the poles and wires

cross fields now, instead of on the turnrows.

Those sections needed deep wells

to change from desert to farm,

so you got filthy men under lonely towers —

drilling two-thousand-foot holes cased with bad postwar steel.

Weakened casings at the perforations,

those first deep wells collapsed when pumped — abandoned.

Drilling crews were asked to move over,

redrill, and case with better steel.

It takes patience, please …

to fill the cylindrical space between casings

and well walls with packed pea gravel,

there’s math involved.

If all the gravel doesn’t surround the casing,

well walls won’t filter and the well dies as a sand pumper.

But if all the gravel packs in the hole, plus a little more,

then long useful deep well lives are lived.

I don’t mean to confuse —

they’re such essential holes in the desert

on the corners of every square mile.

The wells bored down into deep aquifers of ancient water

developed late in the evenings under car lights.

Inside the glow, transplanted Punjabis and Oklahomans

unloaded electric motors, which were copper-wrapped magnets.

Also overcoming the tonnage of Peerless pumps

and forty-foot screwed tubes and shafts —

they’re turbines with impellers inside staged bowls,

lifting and removing salty gray water.

Tractor and irrigation crews

workin’ up and preirrigating sections all summer.

Soon a land collapse began, as shallow aquifers became caverns.

Night tractors disappeared. Exhausted, dusty drivers climbed

from ravines every morning. Eventually the grade

of the elbow plain subsided and fell into rolling hills.

The Cheney was a trap in the subsidence country.

Insolvency in the desert heat.

Hindus with thirty thousand siphon hoses

workin’ both ways from the surveyed crowns

of open ditches to barley or cotton on shifting hillsides.

Main and drain ditches broke down and rearranged slopes.

Ditch breaks were repaired by muddy men while the wells ran —

dangerous to shut down a deep well.

Who knows?

Falling water may unscrew

seven hundred feet of hanging pump.

Swedging’s a waste of an expansion tool —

it means fishing for pumps and losing a swedge:

then you got a worthless swedge down the hole.

It’s crowded.

Winter water, back and forth from barley

and cotton preirrigations, followed by safflower in the spring,

since you can’t ever shut down the deep wells.

The cotton water started in June.

Blooms that survived the shed became bolls;

matured through Labor Day; then got picked and sold.

Always productive, tough to farm, and unlucky —

the Cheney was ours if anything ever was.

Over time, my father imagined hand-moved sprinkler lines

watering the Cheney, instead of hundreds of miles of open ditches.

So the Rainbirds came from industrial desolation

where an Italian carrot grower had sprinkler trials.

They tried portable steel mainlines with bolted flanges,

requiring eight men to make them portable.

Assembled across the middle,

they usually stayed there in the weeds.

The attached sprinkler laterals were made

of thirty-foot joints broken down and moved by Hindus

in deep-well thermal mud to the midthigh.

Changing a dozen quarter-mile lines a day for a dollar a line,

as sun-heated steel burned the hands of line movers.

The Cheney was watered from above by 1953.

Not long after I was born,

the federal portion of the State Water Project

agreed to deliver the Sacramento River

across the lower end of the ranch along the 325-foot elevation.

The canal divided the pattern of things,

as various legal interests resided above and below its course:

the Cheney mostly to the west; and above, the divide.

Clean project water would replace the ruinous salty deep wells,

which could be discarded, abandoned, and sealed.

The federal bureau condemned a right-of-way

and purchased crops within from the ranch in 1968.

Project water moved to the Cheney

through the Manning Avenue buried line —

welded and covered by Leo and Cleo of the Horner Bros.

Those wells became forgotten history —

perforated ghost holes to the dead, resistant seabed.

But the Cheney’s what we’re talking about.

The water came too late.

I come from some of those things …

The “Cheney Spoken” was mostly done,

and Luthor was still away, while warm winter rains

kept pounding the Sierras from the south.

When the storm cleared, all the snowpack was gone.

But needing to see if the poem was right,

I rode an hour west past the Russian town and salt flats.

Bridges still held across the slough,

and people were retrieving their things.

Stopping to roll a Drum on the last bridge —

the cemetery was covered in water

and the only tree was missing.

Smoking, I leaned over the rail

and found it against the pilings,

with quiet water lapping at the leaves.

I left, shaking my head at mobile pepper trees.

Climbing fifteen miles further west

through winter grain and sugar beets;

then I made a southern turn along

the water right-of-way to L.A.

Every couple of miles were bridges across the canal,

and my parents’ old shack on the Cheney Ranch

was twenty minutes away.

Mist ahead sheathed the Coast Range,

and the land below was made by wandering streams.

I passed gently rolling tomato beds

into the subsidence country.

Unnatural hills had vacant labor camps,

and the junkyards grew weeds.

Several fields of unplanted cotton beds

used lines of golf course guns,

shooting evaporative rainbows halfway into the next day.

In the heavier land to the southeast,

my aunt’s unhappy groves cleared the horizon.

Most of my people were alive in the desert —

or dead under shady trees.

Stopping to roll Drums, I smoked one,

and continued past a row of red tractors for sale —

the International kind that don’t shift well.

The canal veered slightly for constant grade;

ahead, someone was fishing for carp.

I smiled because Woodrow, my father’s old welder,

used Camel butts for bait.

Riding closer, I saw it was a friend, Earl Rollinherd,

who’d worked the parts counter for International Harvester —

you know, those red tractors for sale.

“Hey ya, Red Earl, how ya doin’?”

“Goddamn, is that you? We heard you were dead;

heard lots of things — trouble, Roy. You all right?”

“Been off and away doing motorcycles around, Earl.

I don’t farm anymore — been thinking about writing.”

“You ought to, goddamn right —

the dust’s coming, Roy, and your people did so much —

it’ll all go to hell.”

The south wind gusted a little more.

“It’s there now, Earl. Gotta punctuate it somehow.”

Earl was as wrinkled as the land.

His suntans looked holed and worn,

and his glasses were askew.

Said his wife had passed three years before —

buried her outside of Russian town by the pepper tree.

I just nodded at the canal,

while Earl shaded a color grayer at the water —

pulling at his line, as he kept winding it in.

“Roy, I got my yellow Buick working for your dad,

and met your mother as a young woman

wearing pearls in the hell hole.

Rains came, and our cars screamed the Christ outta there.

Tires chained to go in the mud: pavement’s twenty-one miles away.”

Pausing to throw his line, he watched it land.

Then he asked if Mom survived.

I said no.

“Your mom’s gone — that’s too bad.

She was a good one: woman had dust — that shack.”

My mother’s death embarrassed him a little;

so he waved his cracked hands, a finger missing on the right one …

so he wove into his sense of how jerry-rigged things were.

Working every day in the heat, irrigating off hill ditches —

a fuckin’ nightmare. Goddamn nights spent fixing ditch breaks

with lost bulldozers in the salt mud — or plowing the

shit outta the ground, then dragging it to smooth.

“You weren’t alive for those old cart planters

tied behind a crawler and taken out to flat plant:

tool bars, six gangs of two rows behind the pull crawlers.

Those twelve rows looked a mile wide,

with twenty-foot hanging markers outside.

Don’t kill the power pole turnin’, man.

Good day, thirty poles flat planted, sundown.

Hope the wind don’t blow up your butt crack, take it away.”

Always behind the smell of beer, old kinds as Earl talked on.

“Roy, you know the story of Ostraller’s Big Kid?”

“Yeah … yes, I do. Gotta run, Earl. Take care. Good-bye.”

Clouds gathered as I came off the canal …

circling hilly sections one by one, half of them fallowed

because of redefined surface water rights.

Deep wells were groaning for cotton and small grain.

Then the Cheney undulated through

unpruned vineyards and a section of garlic.

Enduring wet lines of ambiguous garlic,

the clove divides became mud-rutted middles,

and a few led to the broken shells of twin gins.

Old men with garlic dangling from their necks to stem the evil.

A nation needs garlic in the rotations.

I rode up above the 500-foot mark across I-5.

Weather building both ways over the land

forced me to time the storm break.

Deep loam falling away into several farms.

I saw too much lease to hold and not a good place to farm

since the water rights had gone to L.A.

That shack — my parents’ first home —

leaned with the wind four miles southeast of me.

I remembered split pictures of a hard dirt road

lined with thousands of barley sacks,

leading to the two rooms of that flat shack.

The air was clearest then — not a tree for fifteen miles.

I wondered if the legs still showed inside old boundaries.

In those days, the Cheney grew skip-row cotton —

four rows in, four out; the Feds paid us for the outs,

we sold the ins on the domestic market.

Half the ranch cotton striped. Four-row cultivate

on the ins, and run a disk up the outs to get the weeds.

Good men could do six poles a day, sundown.

When the sprinklers arrived,

it was productive — but still hard farming.

The Cheney was known for its exotic crew.

I remembered morning gatherings at the shop —

Hindus, and Leo, and Cleo, and Woodrow Wilson Jones.

Woodrow was a butt crack who welded when things broke.

If that didn’t work, he cut it with a torch; if that didn’t make it go,

Woody spit a mouthful of snuff on it and called it “a mare’s ass.”

The Cheney tried growing cannery tomatoes,

sprinkled up from tiny seed down on your knees

as spring winds crossed beige ground.

Checking brown seed rows.

The summer harvest was hard.

Tomato harvesters were shaking machines

full of belts and chains driven by Model-A engines;

dusty forklifts; huge crews sorting out greens;

breakdowns; wheel tractors and harvesters stuck on ditch lines.

Six weeks of sunrise to sunset.

Endless repairs to machines parked in mudholes,

after Hindu boys washed them down with fire hoses every night.

Our first year was all right,

so the tomato acreage expanded.

Cannery died the second year,

leaving the Cheney unpaid after the harvest.

Summer rains brought crop failure the third year.

Tomato scald and a weak world cotton market followed.

… And we’ve almost come to Ostraller’s Big Kid —

a civil, evil kind of guy.

The Westside ranch was staggered by two disastrous tomato crops —

also wallowing in a bad cotton market, with all its cash

tied up in immature Eastside citrus.

In the wake of tomato failure,

a tenth of the Cheney cotton acreage

was on the right-of-way sold to the Bureau.

They owned the crop within, and the Cheney acted as agent

to protect the Bureau’s interests.

Ostraller’s Big Kid’s idea was a stroke of genius —

the only one he ever had: Steal the federal cotton …

my father was away, and it’s a big ranch.

Go in at night for the confusion.

The Big Kid’s problem was gettin’ to the inside man;

and he had to have cash and machines, drivers, trailers.

So the Kid found Cidro Ochoa,

a local contract picker and bar owner.

Cidro’s cash paid off the inside man,

Gene — the Cheney comptroller.

Running Cidro’s machines,

they started picking on a Friday evening,

picking late in the breeze

and again all of Saturday night — with no dew.

They left Sunday morning.

That afternoon, my father

followed cotton-trailer tracks down dirt roads,

which was easy since their aircraft tires left distinctive marks.

In the evening, he got to a windy gin yard —

a single cotton bale left behind in the gin moats and trash …

grown and stolen from the Cheney Ranch.

Hackman, the ginner, never split the sale money

and left the country, which enraged Cidro —

who proceeded to beat Ostraller’s Big Kid blind.

Old man Ostraller paid the medical bill before he threw his kid away.

My father fired Gene on Monday.

Our lenders almost owned the Cheney.

The following year the entire ranch was planted to cotton.

World markets crashed as constant south winds changed the pattern.

The Cheney got unloaded at a fire sale that wet winter,

to a Pittsburgh man who died three months later.

Gene cuts hair in a barbershop in rainy Susanville now.

Cidro Ochoa almost burned to death

in his underwear in a topless bar in Fresno.

They say I came along after Dad took Mom to the hospital —

born on a May dawn with snow in the desert,

as our cotton died and everyone worked like hell replanting:

it’s a wonder they didn’t name me Jonah.

I became the boy searching tool-yards

of faded junk cut by Woodrow’s torches —

farming shapes and farming names that Woodrow reformed

with acetylene and oxygen into simple wheel weights or float drags.

Years passed before we survived on better land.

Below me, the wind misused sprinkler water.

A broken mainline valve spewed fifty feet in the air —

the wind took it a ways, and the Cheney’s odd every day.

The spume’s a rainbow.

Away from the rise, back downhill into storm time,

as the sun crept behind the mountains,

the wind-borne sound of motors and sprinklers

caused me to remember sprinkler nozzles —

with big-ass orifices allowing the sand and salt through.

Drops as big as windshield bugs,

which shook the cotton on impact — I could see that.

I sat listening to chattering Rain Birds

while the south wind whipped that spray.

Nearing the end under clouds stacked above the evening,

I turned toward that shack leaning shaken by the south wind;

stored junk inside kept the walls from falling in.

I withdrew a salt-encrusted Rain Bird — a fine gray one —

and rode a half mile up to the metal pump station.

It’s badly holed; pocked metal sheets rattle,

reflecting the Cheney at dusk.

The oil companies’ stationary ship engines were sold,

leaving a ruin of pitted cement and ribbed walls

beneath the metal pound. What’s left

is a cracked north-south lonely chapel on the west rise.

We should be grateful, gone from the Cheney trap —

where the surrounds are other remains and Dave Cheney’s legs.

The legs … the legs are around somewhere.

I tossed the Rain Bird onto a rusted pile,

while the wind made noise and rain poured.

Wild Cheney’s legs had gotten away.

I slept wet that night in the pump station,

and the storm cleared late the following morning.

Going south along the canal away from Cheney’s trap,

I spent the afternoon in Devil’s Den drinking beer …

Feeling estranged from my source,

I paid for my beer and left the dry end of history,

written as sunburned dumb with empty gins

or faded tractors without wheels.

Outside of Devil’s Den, the asphalt climbed

past the prison where Luthor Rollins used to teach;

and forklifts stood up new walls,

using the tilt-up construction technique.

Beyond the prison were hills with fenced grass

and grazing cattle, surrounding a tangled windmill frame.

I turned at the narrow gravel, thinking there are several Devil’s Dens:

There’s one at Gettysburg. This one had Noah’s house trailer

and a large muddy engine under a pole barn —

with the prison down below.

My first Water Buffalo came in a trade for a similar rain machine;

Noah must have gotten another out of the creek.

I parked the bike, and a few steers stumbled off

while I checked over Noah’s work in progress: he’s a metal sculptor.

His sculpture looked like a shattered engine, with a holed

block and weeds grown from the hole —

disinterred and still wrapped in retrieval chains.

Chain-scarred iron with a stench —

the entire thing smelled of pesticide.

I left Noah’s accidental sculpture for his wide-open door —

he was long gone and dust covered everything inside.

An old grimy desk was set against a shattered window;

one piece of wadded paper was still on the sill.

Without knowing why, I reached and unwadded it.

The opener read:

Robbin’ the Mars Drive-In …

Must have been one of Luthor’s.

I folded it into my pocket before sitting at the desk

and staying up late in an imagined journey.

Eventually, the big engine outside

reminded me of diggin’ out the rain machine.

I unfolded Luthor’s poem and started writing on the back

about the day Noah and I drove an old flatbed truck

away from the morning sun:

The desert was softer beige along the wash.

Water shed east, then to the north through the alluvial fan.

Fractions of rough tamaracks lined the banks;

old rusting cars were thrown in the gaps for erosion control.

Better land came from the creeks:

some pieces grew onions and garlic;

the rest were a nation of unfarmed squares.

Tractors showed distress and age.

Irrigators changed water on the quarter-mile line.

Westside sounds were strange and misunderstood for miles.

It was a muddy afternoon down in the wash.

I saw a camp kettle on the gas stove;

the sun went down while I lit the burner and thought it through.

After a while, the banged-up kettle began to boil;

I found some coffee crystals in the darkening trailer and did the pour.

Outside, it seemed chilly in the grass —

coffee warmed my hands; prison lights lit the town.

Noah’s accidental sculpture …

Inside, I sat at the desk again.

There was a candle in a drawer.

I lit it from the stove and continued writing:

A place on the edge of itself in a valley of the same name.

After crossing that out,

I kept writing. It was cold and dark at the finish.

I relit the candle and a cigarette,

and read aloud what I had written:

Engines were used to move water.

Not too bad. I tried it again …

Diesel driven pumps were mounted on sleds

and used to boost water from deep wells to distant fields.

They were ugly — jerry-rigged by people named Irvin or Woodrow.

Over seasons, heavy sled-mounted pumps

acquired a clothing of grime — a sheathing of smoke-oily mud —

housed between ditches in mud slums.

My Dad called them “rain machines.”

Cidro Ochoa farmed section 35 across from our place,

growing summer cotton and winter barley grain.

His aging stationary engine was lathed and assembled in Moline.

Most of its working life was spent around Cantua,

mired in years of distressed lifting — rings and bearings almost

memories — unable to restart, living a lifetime pumping sentence:

It had no sense of self, knowing only internal explosive strife;

bound to move water, and the end was coming.

With no future after that — not even reformation

into a ship or something.

With Cidro watching through June, July, and into August,

the machine staggered, drinking oil to stay alive.

It died in an agony of expansive hot metal on August eleventh.

A thrown rod shattered the crank and block.

But the dawn-side deep well kept pumping, bursting the iron flanges —

making a cooling wash for the death boil of the Rain Machine.

Enraged, Cidro rolled it end over end.

Bulldozing, screaming, he shoved it over the bank —

joining old cars serving as erosion barriers in flood times …

eventually covered in a silt and mud grave … forgotten.

Holding the bank a generation,

the iron scarred and valleyed from rust.

The Rain Machine resurfaced after the creek changed its course.

Downstream litigation cambered the channel,

exposing the pitted iron to light on our Cantua Ranch.

Noah and I retrieved the scarred old junk

and hauled it to his pole barn.

It sat a little while before the sculptor was ready.

He restored and painted half of the engine block sun yellow,

and welded Murphy switches and Go-Devil blades to the flywheel.

Inserting shanks in the holed block,

a flat bar was added, clamped tightly as mast and crossbar —

all remounted on a drag sled and named “Moving Water.”

Noah sold it to an art dealer on the coast.

It fountains quietly in front of a bank in Mill Valley now.

In his later years, irrigators said Cidro Ochoa

reformed old tools for pleasure, though they seldom worked well.

Abusing the grinders and vises,

he died beating disc spools with a sledge —

just prior to Noah’s resurrection of the Rain Machine.

Cidro was a cheater pipe of a man …